Childhood obesity is a significant global public health concern that has escalated since the late 20th century. In 2022, an estimated 37 million children under the age of 5 were overweight and over 390 million children and adolescents aged 5-19 were also overweight, of which 160 million were obese. Significant research has identified the association between obesity and increased cancer risk, including a study that has specifically found a correlation between high early-life body-mass index (BMI) and an increased risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) in adulthood.

Obesity can have detrimental effects on nearly every organ in a child’s body. The CDC reports that approximately 14.7 million children and adolescents in the U.S. were obese during the period 2017-2020.

Risk Factors of Childhood Obesity

Childhood obesity is a condition in which a child has a significantly higher weight than what is typically expected for their age and height within a specific age range. Since children are continuously growing, the ranges of height, weight, and BMI vary based on age and sex-specific percentiles rather than the BMI cut-points used in adults. However, severe obesity in children can be classified into two classes:

– Class 2 obesity: BMI range between >120% to <140% of the 95th percentile for BMI >35 kg/m2 to <40 kg/m2, based on age and sex.

– Class 3 obesity: BMI >140% of the 95th percentile or BMI >40 kg/m2, based on age and sex.

Several risk factors may contribute to childhood obesity, including:

1. Genetic factors: Both common and rare genetic variants that affect gene expression or function can contribute to obesity. Genetic factors are considered responsible for 40% to 70% of an individual’s obesity risk.

2. Diet: Young people are more likely to consume fast food, processed snacks, and foods rich in processed sugar. These foods often contain higher levels of carcinogens and mutagens, as well as being high in calorie count. California has taken measures to ban four additives commonly used in foods, particularly snacks for children, that have a strong correlation with cancer: brominated vegetable oil, potassium bromate, propylparaben, and Red dye 3.

3. Sedentary lifestyle: Play is a crucial aspect of child development, affecting physical, mental, and social development. The prevalence of video games and the virtual world among children and adolescents has led to a decrease in outdoor play. A study found that over 90% of children over 2 years old play video games, with many spending 1.5 to 2 hours per day gaming. This can contribute to health problems, including obesity.

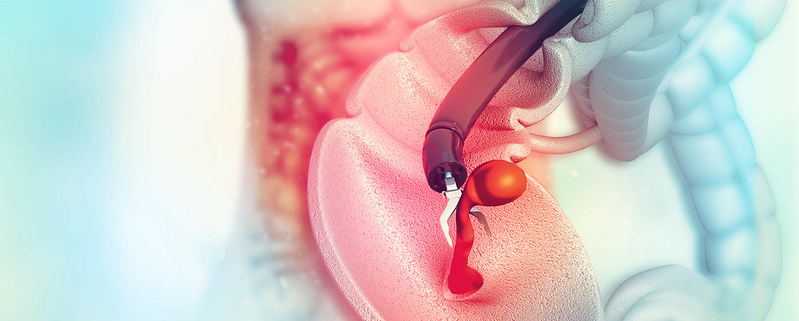

CRC and Obesity

A meta-analysis study in the U.S. involving over 4.7 million participants (3.2 million men and 1.5 million women) found that individuals who were obese in their early life had an increased risk of CRC as adults. The study demonstrated a 39% increase in CRC risk for obese males in early-life and a 19% increase for obese females in early-life, compared to controls. For men, an obese BMI in early life was more strongly associated with distal colon and rectal cancer. In women, the association was stronger for rectal cancer.

Additional studies are needed to fully understand the association between early childhood obesity and CRC risk to prevent cancer in adulthood.

Emmanuel Olaniyan is a Colorectal Cancer Prevention Intern with the Colon Cancer Foundation.

Image by kalhh from Pixabay