By Parker Lynch

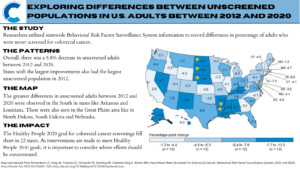

According to the national census data for 2020, Kentucky was found to have the highest incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) in the country—41.2 new cases of CRC per 100,000 people in the state that year. This number is concerning, especially when comparing it to other states with significantly lower rates: Utah, Colorado, Delaware, Arizona, and Vermont (about 20 new cases per 100,000 in 2020).

Why Is CRC Incidence High in Kentucky?

There are several risk factors associated with CRC: tobacco use, poor dietary habits, lack of exercise, genetic predispositions, etc. Unfortunately, the residents of Kentucky exhibit each of these poor lifestyle habits much more than other states. Two-thirds of adults in Kentucky are overweight, less than a tenth eat a sufficient amount of fruits and vegetables, and more than a third are not getting enough exercise. On top of these, family history of CRC is common among many families in the state, making it much more likely for individuals to develop the disease.

On a national level, Kentucky is known for having some of the poorest diets, which includes a regular consumption of fried foods, meats, and bread. Fried foods and over-processed meats, in particular, can expose one’s body to carcinogens that have been linked to CRC as well as various other cancers.

Kentucky Culture

Born out of Corbin, Kentucky, Colonel Sanders’ fried chicken restaurant quickly grew to become a very popular and profitable chain of fast food spots. Known for serving bowls, pot pies, mashed potatoes, and loads of fried chicken, KFC has been a hot-spot since the 1940s. It might seem like an easy fix to tell residents to just “eat healthier”, but unhealthy diets that are deeply ingrained in a state’s culture and history are very hard to just simply eradicate.

Telling residents of Kentucky to stop eating their fried foods is like telling residents of New York to stop drinking coffee; they may just laugh in your face. Changing the standard American diet and encouraging healthy eating habits remains a challenging endeavor for healthcare workers, researchers, community educators, and the population itself.

Educating Communities

For starters, access to dietary and lifestyle counseling should be expanded throughout all states in America. In doing so, people would inherently have the opportunity to reflect on their own eating habits, and create plans to maximize their nutrient intake, while also learning how to be financially feasible in doing so. Many people may not even be aware of the significant health consequences of their dietary habits, and they will never know unless people are intentionally educating communities about these crises.

People don’t need to entirely restrict certain foods in order to avoid CRC, but a gradual decrease of the consumption of fried/heavily processed foods while simultaneously increasing the consumption of vegetables, fruits, and leaner meats will lead to a new culture: one where CRC is not a common disease in one’s community or town.

Parker Lynch is a Colorectal Cancer Prevention Intern with the Colon Cancer Foundation.

Picture credit Larry White from Pixabay.